Flying Blind: The Early Days Of Rotary-Wing Aviation In The Marine Corps

With the advent of the marine helicopter in the late 1930’s, there came this idea of “vertical envelopment.” That’s the ability to pick-up and drop-off equipment and troops in remote environments. Specifically, without a runway. This capability was quite appealing to the U.S. Marine Corps. Shortly after WWII, they began to develop their first rotary-wing program.

Marine Helicopter Pilots

Seasoned WWII fighter pilot Colonel John “Big John” LaVoy was selected to be one of the first Marine Corps pilots to be trained to fly these aircraft. A captain at the time, LaVoy joined the inaugural class of helicopter pilots in Pensacola, Fla. in 1944. All of the candidates were accomplished fixed-wing pilots. However, as they soon found out, helicopter flying was completely different than anything they had experienced before.

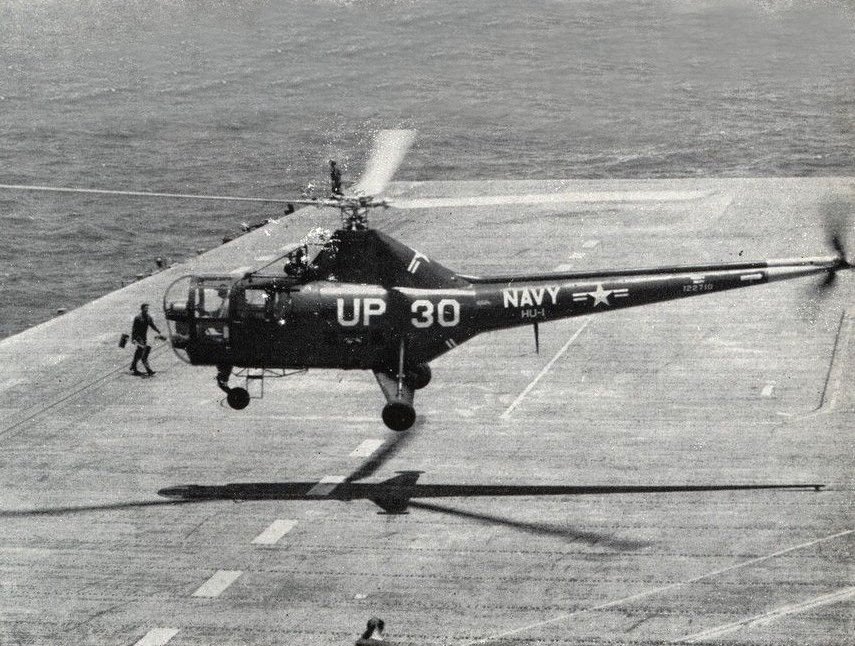

LaVoy and his fellow freshly-minted marine helicopter pilots joined Marine Observation Squadron 6 (VMO-6) shortly after North Korean forces invaded South Korea on June 25, 1950. The crew set off for East Asia. This squadron was the first one from the USMC to have helicopters attached to it. They were originally deployed on the escort carrier Badoeng Strait with four Sikorsky HO3S-1’s in tow.

However, due to their poor in-flight stability, lack of cabin space for passengers and stretchers, and difficulty landing in rough terrain, the HO3S-1’s proved to be non-ideal for in-theater operations. Bell HTL-4’s – the helicopter popularized by the hit TV show M*A*S*H – soon replaced the Sikorsky’s.

The HTL-4’s handled the Korean terrain better than the HO3S’s, but they were still far from perfect. For example, the navigation equipment on the helicopters was primitive. Many times they went on missions to rescue a pilot that was shot down or to transport wounded Marines, with nothing more than a simple map to guide them. The instrumentation was so poor that the aircraft was never officially certified for night flight. However, with the lives of U.S. servicemen on the line, John LaVoy and his fellow pilots soon found themselves defying orders and flying medevac and rescue missions after sundown. Other branches followed suit and these dangerous, late-night missions without navigation soon became the norm.

Heroic Efforts

Sometimes the bulbous front windshield of the marine helicopter fogged up, reducing their visibility. When this happened, they turned the aircraft sideways to fly at an angle so they could see out of the side doors.

The weather in Korea didn’t make flying any easier either, especially in the winter. Often times the cloud line was very low to the ground, which meant that they would need to fly even lower in order to be able to see where they were going. LaVoy and his men flew so close to the ground that they dipped below power lines and over trucks on the road. Such flight maneuvers would be completely unthinkable to modern day helicopter pilots.

Many times the pilots of VMO-6 were sent on rescue missions deep behind enemy lines. The pilots closed in on a landing zone and were immediately bombarded with rocket and gunfire. This flying was extremely dangerous but LaVoy and his men persisted, flying rescue and medevac missions 7 days a week, for the entire year of their deployment.

Thankfully, marine helicopter flying has improved a great deal since the days of Korea. The training is more thorough and the aircraft themselves are much safer and easier to operate. One thing is certain, though; the USMC rotary-wing program would not be where it is today were it not for the efforts John LaVoy and the Marines of VMO-6. Their bravery, ingenuity, and unwavering sense of duty allowed a fledgling technology to develop into a powerful component of our modern military capabilities.